The landscape of electronic design is always changing, largely due to the increasing complexity in printed circuit board (PCB) layouts. As devices shrink and performance demands grow, manual design methods frequently present bottlenecks. This isn’t just about speed; it’s about the ability to address multifaceted constraints concurrently, significantly reduce costly errors, and the like. Here, generative AI for PCB design emerges as a positive shift, offering a compelling return on investment (ROI) that strategic planners can’t ignore. This article delves into the tangible data and metrics that underscore the financial and operational benefits of adopting generative AI for your PCB design workflow.

Generative AI for PCB Design: An Evolving Approach

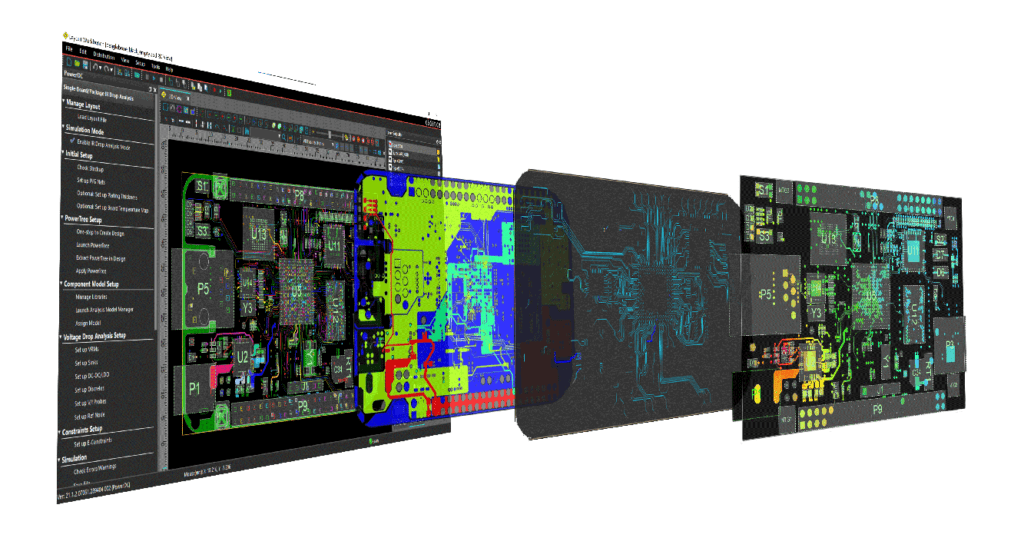

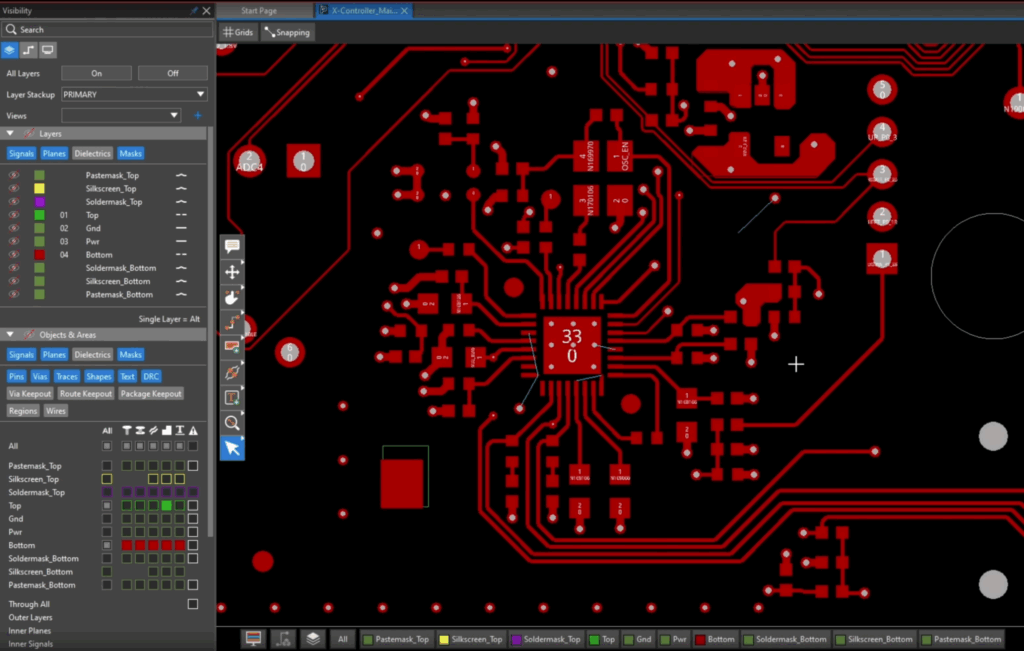

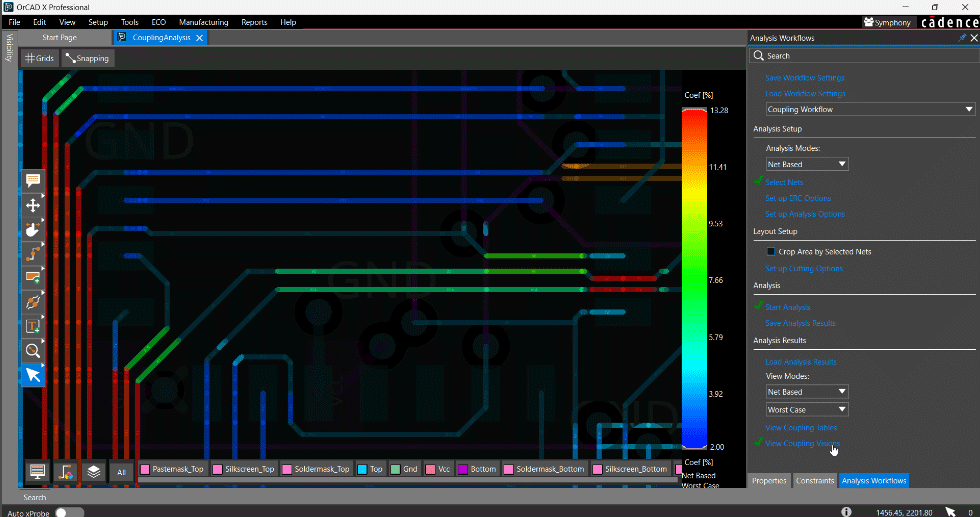

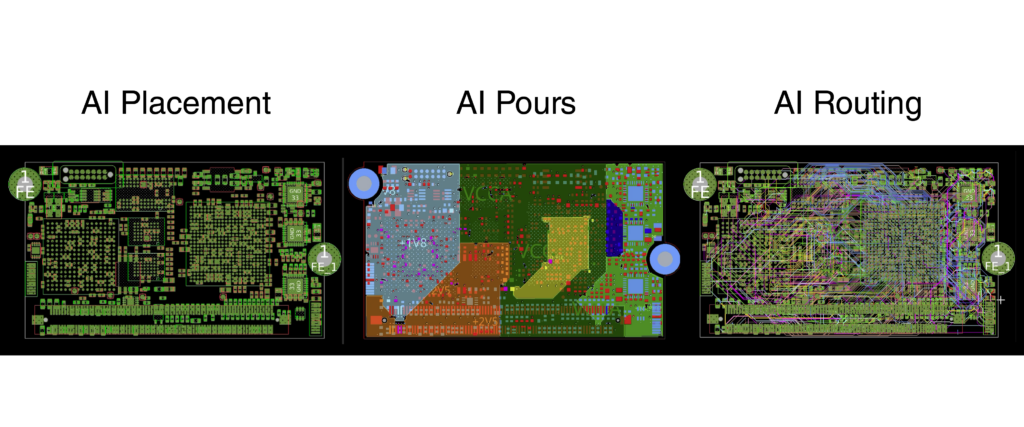

Generative AI for PCB design refers to machine learning models that autonomously craft designs by learning from extensive datasets of existing board layouts. These systems grasp design constraints and performance objectives, generating new board topologies and routing paths. Unlike traditional rule-based automation or reactive AI optimization, generative AI proactively proposes solutions, exploring thousands of configurations in hours rather than weeks. For instance, tools like Cadence Allegro X AI leverage generative AI to automate component placement, critical net routing, and overall layout optimization.

Generative AI is changing PCB workflows through:

- Intelligent Component Placement: AI algorithms optimize component placement, accounting for factors such as signal path lengths, thermal coupling, power-delivery network efficiency, manufacturing constraints, and EMI/crosstalk minimization.

- Automated Routing with Performance Constraints: Advanced routing engines, powered by machine learning, can simulate and iterate faster, applying impedance control, trace spacing, and via placement rules simultaneously.

- Design Space Exploration: Instead of engineers testing one or two board variations, generative AI can swiftly explore thousands of potential configurations, leading to optimal solutions for performance, cost, and manufacturability.

Quantifying the Return: Key Metrics and Data

The financial benefits of generative AI aren’t speculative; they’re measurable through several key performance indicators.

Market Expansion Fueled by AI

The broader Electronic Design Automation (EDA) market is poised for significant expansion, driven directly by AI. Bloomberg Intelligence forecasts that AI could add a substantial $6 billion in value to the EDA market by 2030, projecting the total market to reach approximately $23.9 billion with an 11.8% Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) from 2024-2030. However, this growth isn’t just about new tools; it also reflects a fundamental enhancement in engineering productivity and design capabilities.

Time-to-Iteration: Compressing Design Cycles

One of the most compelling metrics for generative AI’s impact is its ability to cut down time-to-iteration. Manual processes, often involving days or weeks for layout and optimization, are being transformed into hours or even minutes.

Consider the following design iteration time comparison tests, from real engineers:

| Design Task | Manual/Traditional Design | Generative AI Design | Time Reduction |

| Complex 8-Layer Board Routing | 2 Days | 47 Minutes | ~96% |

| 847 Component Placement | 3 Days | 8 Minutes | ~99% |

| High-Density PCB Placement | 3 Days | 75 Minutes (plus a 14% improvement in wire length) | ~98% |

| Typical Layout Iteration | Weeks | Hours | ~90% or more |

This acceleration means engineers can cycle through more design variations, test hypotheses earlier when changes are inexpensive, and refine concepts with faster speeds than ever before.

Error Reduction: Fewer Rework Cycles, Lower Costs

Design flaws are costly. Reports suggest that as much as 30% of project costs can stem from reworks due to design errors. Generative AI mitigates this risk by identifying potential issues early in the design phase, before expensive physical prototypes are made.

- AI algorithms detect design flaws, such as signal interference or power distribution issues.

- AI-driven Design Rule Checking (DRC) has been shown to reduce errors by 25%.

- Modern AI systems excel at catching subtle spacing violations, signal integrity problems, thermal hotspots, power distribution inadequacies, and Design for Manufacturability (DFM) violations that are often overlooked. This preemptive error detection translates directly into reduced scrap, fewer costly board respins, and lower overall manufacturing expenses.

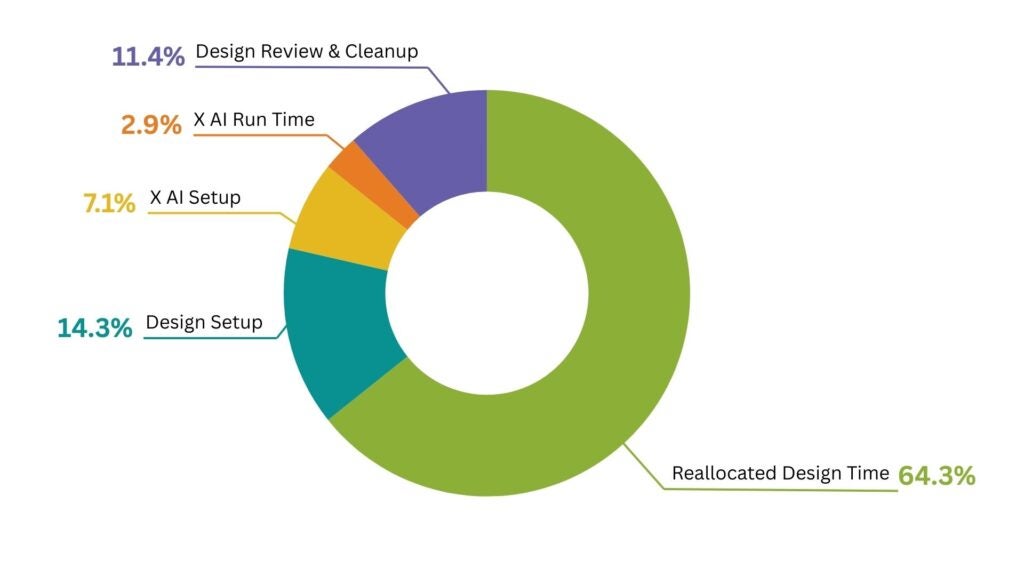

Design Automation Rate: Freeing Engineers for High-Value Work

Generative AI excels at automating repetitive, compute-intensive design tasks, thereby increasing overall design automation rates. This frees up senior engineers to focus on higher-value activities like architectural innovation, complex problem-solving, and strategic planning.

- AI algorithms can automate component placement, trace routing, and power plane creation.

- AI-powered tools can achieve 90%+ completion rates for auto-routing complex boards, a feat that was impossible just five years ago.

- Specific tasks often automated include:

- Optimal component placement considering electrical, thermal, and mechanical constraints.

- Critical net routing, ensuring signal integrity.

- Design rule compliance and manufacturability checks.

This automation directly increases engineering productivity by more than 5x on some chip design tasks, allowing teams to accomplish more with existing resources or reallocate talent.

Strategic Implications and ROI

The data paints a clear picture: generative AI for PCB design delivers a compelling ROI through accelerated development cycles, reduced errors, and enhanced engineer productivity. This means:

- Faster Time-to-Market: The reduction in iteration time translates to quicker product development and deployment, offering a competitive advantage.

- Cost Savings: Fewer design errors, reduced rework, and optimized material usage contribute to substantial cost reductions throughout the product lifecycle.

- Innovation Acceleration: By automating routine tasks, engineers can channel their expertise into complex architectural challenges.

- Improved Quality and Reliability: AI’s ability to explore more design possibilities and detect subtle flaws results in more reliable products.

While an IBM report noted a general enterprise AI ROI of 5.9%, the specific direct impact in EDA, particularly through productivity gains from generative AI, suggests a much higher and more immediate return for targeted applications.

EMA Design Automation is a leading provider of the resources that engineers rely on to accelerate innovation. We provide solutions that include PCB design and analysis packages, custom integration software, engineering expertise, and a comprehensive academy of learning and training materials, which enable you to create more efficiently. For more information on generative AI for PCB design and how we can help you or your team innovate faster, contact us.